It is an old axiom in Christian theology, borrowed from the Greek philosophers but supported by scripture, that God is unchanging. The reason for this, on the philosophical side, is that God must by nature be perfect. Any change is, however, either a change for the better or for the worse. Thus, God is immutable. Some points about that idea might be argued, but by and large I agree with it and it is not the focus of my post today.

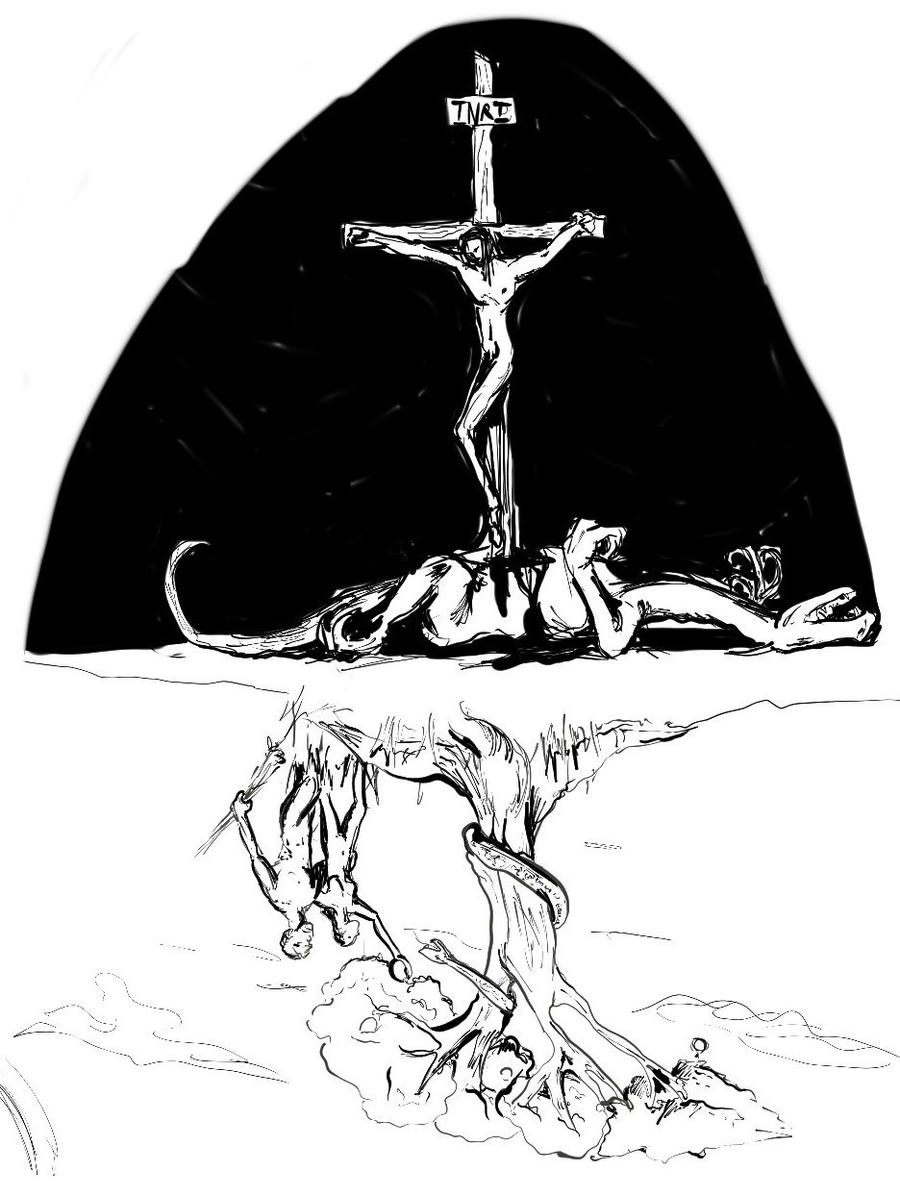

Rather, I want to address a particularly corollary of the immutability of God according to the Church Fathers and most who came after them - that God is passionless. Passions (or emotions) are themselves changes of state, encompassing certain physical and relational states experienced by the subject. Because they necessarily involve change, the Greek philosophers would argue, the passions are necessarily imperfections, and so God cannot have passions. This led to problems for the Church Fathers, who by and large accepted the Greek vision, but who also acknowledged the genuine incarnation of God as a human person who did indeed suffer. In explaining this, the Church Fathers appealed to Christ's nature as fully God and fully man. He suffered passions as a man, but not as God.

Many, including myself, later questioned this explanation. This, in turn, leads to questions about whether or not God's perfection can in fact be understood in the manner the Greeks understood it. I think the answer is both yes and no.

I say yes to the Greeks because I do believe perfection does in fact entail a kind of immutability. God, if He is truly perfect, cannot grow wiser, for then He would be less then perfectly wise. However, I think their understanding that all change is a change for the better or for the worse is at least partially flawed. For some things, the relative virtue of a change very much depends on that to which it stands in relation. For example, if I want to go to the store, which is to the right of where I am currently sitting, a turn to the left would be bad, while a turn to the right would be good. Lacking a goal, any turn would, of course, be neutral. This, as of yet, does not defeat the Greek's point. For, that I can turn either to the better or to the worse relative to my goal and I am thus not in the best of all possible positions (i.e. perfection) in which no change could either improve or worsen by case.

What then, of passions? Passions themselves are, I believe, good or bad depending very much on circumstances. Fear is a good and appropriate emotion when faced with danger, but bad if it is in response to something neutral or helpful. Important in the world of passions is the conditioning of the emotional system. The perfect emotional being would always have the proper emotional response to every possible stimuli. Few of us, of course, have this. Even the most healthy mind might find itself experiencing fear at a needle bearing beneficial medicine. The point here is that fear is always good/right/fitting when facing genuine danger and always bad when not facing genuine danger. Though our emotional lives are often an admixture of the good and the bad, there is an ideal emotional state in which a change in emotions is not a change for the better or the worse, but simply the appropriate response to the stimuli at hand.

My contention is that God, especially an incarnate God, can in fact have passions without those passions being changes for the better or worse, but instead appropriate. It is appropriate for God to have anger at sin, love for His creatures and joy in their salvation. Moreover, if God incarnates, then it would be appropriate for Him to experience fear at the threat of crucifixion or anger at corrupt and heartless religion.

Divine passions would, of course, not look fully like ours (human language

must always fall short in describing the perfect being afterall). Certainly, God the Father would not experience the physical change of state that we associate with emotions. Questions of temporality come in too, but dealing with that is outside of the scope of this article.

So is God immutable perfection? Yes, but that does not mean he is without appropriate passions. Understanding always, that until we meet Him face to face, we always see as in a mirror darkly (1 Corinthians 13:12).

_______________________________________________________

1. By English: Unknown Español: Desconocido Français : Inconnu (Luis García (Zaqarbal), 27–September–2008) [

GFDL or

CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0]

_(wascDA0181).jpg)